Imagine tens of thousands of insects smaller than a flea infecting, hatching and crawling all over your skin.

Welcome to world of some deer in California.

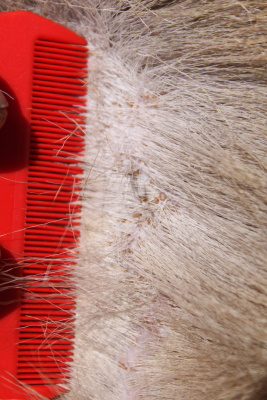

Researchers at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are studying a hair-loss syndrome across the state – a condition that originates with tiny non-native lice that infect California deer causing them to scratch, bite and basically pull out their own hair.

“Think of it like a really bad flea infestation on your pet, but a lot worse,” says CDFW senior wildlife biologist Greg Gertenberg who is tracking reports of lice on deer across the state, mainly in mountains of Northern California, but now it appears to be moving into – or already here – in Southern California. Gertenberg says lice samples have been taken from deer in Santa Barbara and San Diego Counties.

In some cases, deer are also stricken with a heavy infestation of internal parasites.

Gertenberg explains the lice are so irritating on the skin, that deer will constantly groom which makes their coats look scruffy and even produce bald spots. With all this grooming, deer forget to eat, become weaker and probably won’t be paying attention when mountain lions and other predators are eyeing them from afar.

In addition, the lice makes it difficult for fawns to survive — which could eventually impact all California deer.

There are basically two types of non-native lice that researchers are targeting – the exotic fallow deer louse (which bites hosts) and the African blue louse (which sucks their hosts). The African louse has been in the states for a number of years – the biting fallow deer louse is a new major concern because it reproduces asexually with only females.

“We are concerned about [fallow deer lice] rapidly spreading,” says Gertenberg whose team has been studying lice and deer since 2009. “We know we can’t get rid of the lice completely – there’s no way to treat an entire population – but we want to determine the impact on the deer and what we can do to minimize that impact.”

Part of the puzzling aspect of the deer-lice relationship is that in one herd examined 80-95 per cent of deer have lice, but surprisingly some deer have none, others only a few and then others could be crawling with the creepers. Researchers want to find out what the differences are and how to best help deer. Does it mean change the habitat? Food options? Mineral deficiencies?

To date, researchers have successfully captured and collected hair and blood samples from more than 600 deer and elk across California.

Researchers have been counting and identifying lice on each deer, applying radio collars to track the deer, and treating some deer for lice.